American Virtù: Discourses by Michael Anton

Students of ‘intellectual Trumpism’ will be interested in parts of this recent interview with Michael Anton upon his leaving the National Security Council to take up a fellowship at Hillsdale College. Under the pen name Publius Decius Mus, Anton was the author of probably the single most consequential political article during the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign, the electrifying ‘Flight 93 Election,’ an assault on mainstream (so-called 'Never-Trump') conservativism which it is worth quoting at length:

“2016 is the Flight 93 election: charge the cockpit or you die. You may die anyway. You—or the leader of your party—may make it into the cockpit and not know how to fly or land the plane. There are no guarantees.

Except one: if you don’t try, death is certain. To compound the metaphor: a Hillary Clinton presidency is Russian Roulette with a semi-auto. With Trump, at least you can spin the cylinder and take your chances…

One of the paradoxes—there are so many—of conservative thought over the last decade at least is the unwillingness even to entertain the possibility that America and the West are on a trajectory toward something very bad. On the one hand, conservatives routinely present a litany of ills plaguing the body politic. Illegitimacy. Crime. Massive, expensive, intrusive, out-of-control government. Politically correct McCarthyism. Ever-higher taxes and ever-deteriorating services and infrastructure. Inability to win wars against tribal, sub-Third-World foes. A disastrously awful educational system that churns out kids who don’t know anything and, at the primary and secondary levels, can’t (or won’t) discipline disruptive punks, and at the higher levels saddles students with six figure debts for the privilege. And so on and drearily on….

A Hillary presidency will be pedal-to-the-metal on the entire Progressive-left agenda, plus items few of us have yet imagined in our darkest moments. Nor is even that the worst. It will be coupled with a level of vindictive persecution against resistance and dissent hitherto seen in the supposedly liberal West only in the most “advanced” Scandinavian countries and the most leftist corners of Germany and England. We see this already in the censorship practiced by the Davoisie’s social media enablers; in the shameless propaganda tidal wave of the mainstream media; and in the personal destruction campaigns—operated through the former and aided by the latter—of the Social Justice Warriors. We see it in Obama’s flagrant use of the IRS to torment political opponents, the gaslighting denial by the media, and the collective shrug by everyone else.

It’s absurd to assume that any of this would stop or slow—would do anything other than massively intensify—in a Hillary administration. It’s even more ridiculous to expect that hitherto useless conservative opposition would suddenly become effective…Yes, Trump is worse than imperfect. So what? We can lament until we choke the lack of a great statesman to address the fundamental issues of our time—or, more importantly, to connect them. Since Pat Buchanan’s three failures, occasionally a candidate arose who saw one piece: Dick Gephardt on trade, Ron Paul on war, Tom Tancredo on immigration. Yet, among recent political figures—great statesmen, dangerous demagogues, and mewling gnats alike—only Trump-the-alleged-buffoon not merely saw all three and their essential connectivity, but was able to win on them. The alleged buffoon is thus more prudent—more practically wise—than all of our wise-and-good who so bitterly oppose him. This should embarrass them. That their failures instead embolden them is only further proof of their foolishness and hubris…

And if it doesn’t work, what then? We’ve established that most “conservative” anti-Trumpites are in the Orwellian sense objectively pro-Hillary. What about the rest of you? If you recognize the threat she poses, but somehow can’t stomach him, have you thought about the longer term? The possibilities would seem to be: Caesarism, secession/crack-up, collapse, or managerial Davoisie liberalism as far as the eye can see … which, since nothing human lasts forever, at some point will give way to one of the other three. Oh, and, I suppose, for those who like to pour a tall one and dream big, a second American Revolution that restores Constitutionalism, limited government, and a 28% top marginal rate.

But for those of you who are sober: can you sketch a more plausible long-term future than the prior four following a Trump defeat? I can’t either.

The election of 2016 is a test—in my view, the final test—of whether there is any virtù left in what used to be the core of the American nation. If they cannot rouse themselves simply to vote for the first candidate in a generation who pledges to advance their interests, and to vote against the one who openly boasts that she will do the opposite (a million more Syrians, anyone?), then they are doomed. They may not deserve the fate that will befall them, but they will suffer it regardless.”

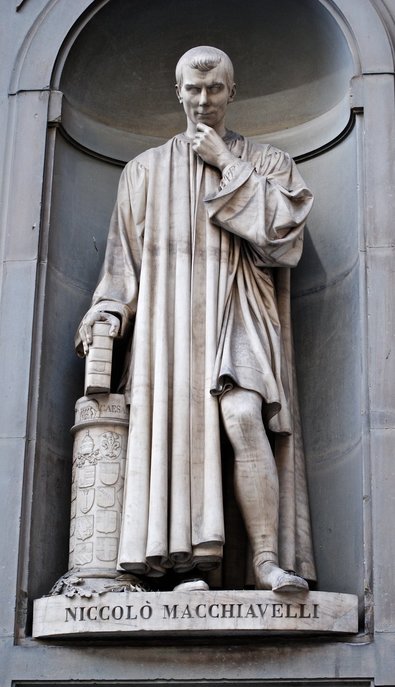

What is the virtù of the American nation that Anton says the 2016 election would test? The term refers to a complex notion in the work of Niccolo Machiavelli, who is, apparently, a political hero of Anton’s, and the subject of his post-graduate work at Claremont Graduate University. According to Bernard Crick’s Introduction to the 1975 Penguin edition of Machiavelli’s ‘Discourses’:

“It comes from the Roman ‘vir’ (man) and ‘virtus’ (what is proper to a man). But what is proper to a man? Courage, fortitude, audacity, skill and civic spirit – a whole classical and renaissance theory of man and culture underlies the word: man is himself at his best when active for the common good – and he is not properly a man otherwise: politics is not a necessary evil, it is the very life. It has little or nothing to do with the Christian concept of virtue and virtuousness – virtuosity is closer to the mark… But ordinarily, as must be plain to anyone who reads The Discourses as well as The Prince, virtù implies a specifically civic spirit. Virtù is the quality of mind and action that creates, saves or maintains cities. It is not true virtù to destroy a city. Hence it always implies a political morality. ‘Civic spirit’ is probably the best simple translation – if by ‘spirit’ one means spirited action…” (Bernard Crick: Introduction to the 1975 Penguin edition of Niccolo Machiavelli, ‘The Discourses.’)

“It comes from the Roman ‘vir’ (man) and ‘virtus’ (what is proper to a man). But what is proper to a man? Courage, fortitude, audacity, skill and civic spirit – a whole classical and renaissance theory of man and culture underlies the word: man is himself at his best when active for the common good – and he is not properly a man otherwise: politics is not a necessary evil, it is the very life. It has little or nothing to do with the Christian concept of virtue and virtuousness – virtuosity is closer to the mark… But ordinarily, as must be plain to anyone who reads The Discourses as well as The Prince, virtù implies a specifically civic spirit. Virtù is the quality of mind and action that creates, saves or maintains cities. It is not true virtù to destroy a city. Hence it always implies a political morality. ‘Civic spirit’ is probably the best simple translation – if by ‘spirit’ one means spirited action…” (Bernard Crick: Introduction to the 1975 Penguin edition of Niccolo Machiavelli, ‘The Discourses.’)

So, do the American people still have the civic spirit, the quality of mind and spirited action to save this city, the American Republic? This remains an open question, of course.

Like Nassim Taleb, another various-minded thinker, Anton is an American of Lebanese descent. He was at one time a speech-writer for George W. Bush, and when he wrote ’The Flight 93 Election,’ a Wall Street executive. Along the way, he worked as a chef in a French restaurant and wrote ‘The Suit,’ a book on men’s fashion in the manner of Machiavelli. Upon Donald Trump ’s election victory, he joined the administration as deputy assistant to the President for strategic communications on the National Security Council.

The majority of questions asked of Anton in his recent interview with ‘American Greatness’ magazine are of the ‘who backstabbed, or leaked or bitched on who inside the White House’ sort. But toward the end there is this Q&A:

Have your positions evolved since you joined the administration? Have you betrayed the “America-First” nationalist populist base?

…The last time my positions “evolved” was in 2015-2016—and that was because of Donald Trump!

I had long been an immigration restrictionist and a believer in immigration reform, so that’s what first attracted me to Trump’s candidacy. I had been drifting away from what a friend calls “naïvecon” foreign policy for years. Trump was offering a clear alternative there.

Trade was the one issue where I was conflicted. I had always been a traditional conservative free trader. Trump prompted me to rethink that. I went back to the old books, the old arguments, and took a fresh look. I’ve always considered myself a Lincolnian—and Lincoln was a tariff guy. Over a period of months, I came Trump’s way on trade.

Not that I think tariffs are always good. Circumstances matter. The United States benefited from tariffs in the post-Civil War industrial revolution, and from more liberal trade policies after World War II. But lately free trade had become an orthodoxy and its advocates are more like priests. Trump was, and is, right that the United States is being taken advantage of. Our country has to do something about that—and he’s doing it.

The slogan I used throughout 2016 was to define “Trumpism” as “secure borders, economic nationalism, and America first foreign policy.” I still support that agenda 100 percent.

I’m not sure what a nationalist-populist is, exactly. I’m a patriot for sure and I don’t think nationalism is a dirty word, as some do. I’m just not entirely clear on what the difference is. I have no problem being called an American nationalist, though.

I also don’t know what a populist is supposed to be now, except that it’s supposed to be bad. I think there are two fundamental reasons why that is, in the current context. First, obviously, is that the word is just a cudgel to use against President Trump. “Populist” has long had a negative connotation—though nobody can quite articulate why—and so the president’s enemies use that negativity against him. Trump is bad, populism is bad, Trump is a populist. QED.

The other reason is unspoken—and unspeakable. Populism is implicitly held to be bad because any popular reaction against the elite-Left-sellout-Right agenda is a threat to the ruling class. So all kinds of perfectly just claims and complaints get slandered and dismissed as “populist.” The purpose is to perpetuate the status quo.

Anyway, if “populism” means actually listening to what the people want and pursuing policies that benefit the majority, even if that is in some ways at the expense of the elite, then I am a populist. The country has to work for all of us. The United States of America was not designed or intended to be an oligarchy.

Fundamentally, I believe in the eternal truths of political philosophy, and that the Founding principles of the United States, as fulfilled via the post-Civil War amendments, are the true ground for just and legitimate government in the modern world.”

Anton says more on populism at this Hillsdale College symposium carried on C-SPAN. The symposium is on a recent collection of essays, “Vox Populi: the Perils and Promise of Populism,” edited by Roger Kimball. Anton's segment starts around the 29-minute mark and includes this comment on the populism of – who else? – Niccolo Machiavelli:

“Machiavelli's 'Discourses' Book 1 Chapter 58 is entitled The Multitude is Wiser and More Constant than the Prince. So this is the first time a political philosopher says any such thing. He specifically praises the people on the specific grounds of wisdom and constancy…As modern examples of the multitude being wiser and more constant than the prince, it was the multitude, after all, the American people, who, for a couple of decades at least were tired of unchecked illegal immigration and the lack of border security, tired of bad trade deals that were hollowing out the manufacturing base and the middle class in flyover country, and were really tired of giving in to wars that Americans didn’t seem to know how to win, or even what the strategic purpose was. Whereas the elites, the Princes who were supposedly wiser and more constant blundered us into all those things, plus the financial crisis and a lot of other things. So who really is wiser and more constant? It’s an open question, at a minimum.”

For a broader take on ‘intellectual Trumpism’ see this article in The Chronicle of Higher Education by Jon Baskin on ‘The Academic Home of Trumpism.’ That’s the Claremont Institute near Los Angeles, headed by Charles Kesler, “a professor of government at Claremont McKenna College, and presiding chieftain of an obscure (until recently) tribe of political philosophers known as the ‘West Coast Straussians’ — named for the  émigré philosopher Leo Strauss. Kesler is also the editor of The Claremont Review of Books, the conservative magazine that The New York Times says is ‘being hailed as the bible of highbrow Trumpism.’ “

émigré philosopher Leo Strauss. Kesler is also the editor of The Claremont Review of Books, the conservative magazine that The New York Times says is ‘being hailed as the bible of highbrow Trumpism.’ “

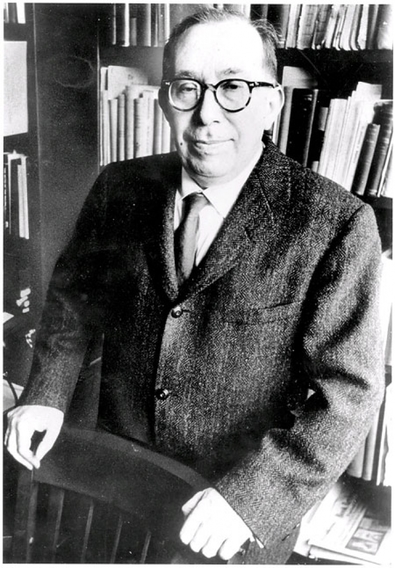

“Both Anton and Kesler identify themselves as "West Coast Straussians," which means they sit on one branch of a family tree whose trunk is Leo Strauss. Strauss, who emigrated to America in 1937, teaching first at the New School for Social Research and then at the University of Chicago (near the end of his career, he taught briefly at Claremont), was known for his painstaking interpretations of the great works of the Western tradition. A student of Heidegger’s and an early admirer of Nietzsche, he ultimately sought to address the "crisis" he believed had been provoked by modern philosophy’s turn away from the animating sources of Western morality: classical philosophy and biblical religion…

The "East Coast" school, of which Allan Bloom, author of The Closing of the American Mind (1987), was the most prominent representative, read Strauss as having endorsed America’s liberal democracy for being built on the "low but solid ground" of Lockean political philosophy. The founding fathers, according to this perspective, had done the best they could given the foreshortened moral horizon of modernity: the American Republic provided peace and security, but it was insensible to what Strauss believed the ancients, particularly Plato and Aristotle, had identified as true virtue or excellence…

But another of Strauss’s students, Harry V. Jaffa, did not agree that America was just another compromised product of modernity. Pointing often to Strauss’s decision to open his book Natural Right and History (1953) with a quotation from the Declaration of Independence, Jaffa, who died in 2015, developed what he presented as a Straussian case for America as a truly great regime, founded predominantly on a combination of Aristotelian and biblical — that is ancient, as opposed to modern — principles…

[Jaffa’s polemics] made the point, rather relentlessly, that for an American political philosopher the pursuit of truth requires the patriotic, and sometimes very public, defense of the "self-evident" truths laid out in the country’s founding documents…

Although the "Flight 93" essay might seem to paint a pessimistic picture of an America experiencing existential turbulence, both its frame and its style reflect Jaffa’s conviction that the country’s political philosophers sometimes have an emergency role to play in its political life. "A core difference between West Coast and East Coast Straussians," Anton told me, "is that we in the West believe there is an urgency to political engagement." As a graduate student under Jaffa and Kesler, Anton learned to be "mindful of the higher plane that is above politics and that informs (or should inform) politics. But also to take seriously Strauss’s admonition not to have contempt for politics." “

Anton also wrote a fine appreciation of Harry Jaffa in the Claremont Review of Books, upon Jaffa's death in 2015.

“Jaffa knew everything, or at least everything important. Much of what will be written about him in the coming days will focus on Lincoln, American politics, and modern conservatism, which is absolutely fitting. But his mind was a museum stuffed to the rafters with masterworks. Name any “great book” and he knew it cold. Books he hadn’t studied for 50 years he could recall in detail, with total clarity. Montesquieu, Machiavelli, Marsilius—all of it. Wondering about an obscure passage in Shakespeare? Ask Professor Jaffa. First he would quote it in full, from memory, and then spend an hour explaining what it meant, in the context of that play, and in Shakespeare’s corpus. The same could be said for Plato—a philosopher about whom, unless I am very much mistaken, he never published a word beyond a passing reference. And not just the Republic and the Apology—he knew all of the dialogues. He knew every book of the Bible. And he knew more about American literature than the entire English faculties of some of our elite universities.

I could tell the following story about any number of books, but I will confine myself to two. I had been obsessed with Moby Dick in my senior year of high school and freshman year of college. I found all the scholarly interpretations unsatisfying. Somehow, one day in the lair, that book came up. Jaffa launched into a lengthy—it must have been at least 90 minutes—interpretation of the whole work: its design, its symbols and themes, everything. It all came together as he spoke. Of course that’s what that means! When he was done I said, “So, Professor Jaffa, you’ve written that up—can you tell me in what journal so I can get a copy?” No, he hadn’t written it up. It would have taken ten lifetimes to write out all he knew. We later had the same conversation about Huckleberry Finn. It remains a source of profound regret that I didn’t immediately try to put down in notes as much as I could remember of what he told me.”

I could tell the following story about any number of books, but I will confine myself to two. I had been obsessed with Moby Dick in my senior year of high school and freshman year of college. I found all the scholarly interpretations unsatisfying. Somehow, one day in the lair, that book came up. Jaffa launched into a lengthy—it must have been at least 90 minutes—interpretation of the whole work: its design, its symbols and themes, everything. It all came together as he spoke. Of course that’s what that means! When he was done I said, “So, Professor Jaffa, you’ve written that up—can you tell me in what journal so I can get a copy?” No, he hadn’t written it up. It would have taken ten lifetimes to write out all he knew. We later had the same conversation about Huckleberry Finn. It remains a source of profound regret that I didn’t immediately try to put down in notes as much as I could remember of what he told me.”